Screening for Dyslexia

What it Does and Doesn’t Do

It would be wonderful if it were possible to perform a quick, simple screening for every child and identify those who have dyslexia. But screening for characteristics of dyslexia is not the same thing as diagnosing it, and identifying children who may have dyslexia is not as simple as screening them for reading skills.

As of fall 2020, 11 SREB states and many other states across the nation require that schools screen elementary students for reading difficulties or characteristics of dyslexia. Both kinds of screening involve performing short assessments of various reading skills to identify students who are at risk of reading difficulties. Those difficulties might be caused by dyslexia, but they can also be caused by other factors.

Identifying students who may have dyslexia — or as states often refer to it, those with “characteristics of dyslexia” — requires a similar multi-step process

A good analogy for dyslexia screening and its limits is the glucose challenge test for pregnant women to identify those who may have gestational diabetes. A woman drinks a special sweetened liquid and then has blood drawn an hour later to measure the amount of glucose remaining in her blood. If the level is too high, she fails the test, but this doesn’t necessarily mean she has gestational diabetes. Women who fail the initial screening then complete a diagnostic oral glucose tolerance test, which involves an even sweeter drink and more blood drawn over a longer period of time. Failing this diagnostic test does result in a diagnosis of gestational diabetes. Together, the challenge test and the diagnostic test that follows can identify 80-90% of women who have gestational diabetes. But if doctors went only by the initial glucose challenge test, they would diagnose many women who don’t have gestational diabetes at all.

Identifying students who may have dyslexia — or as states often refer to it, those with “characteristics of dyslexia” — requires a similar multi-step process. Screening tools are designed to be relatively brief and general, identifying students who are at risk of poor learning outcomes. Their purpose is not to diagnose dyslexia or any other specific learning difficulty, and they are not made to do that. What they do is help educators identify students whose skills fall below a certain threshold, indicating that the student needs additional support. Some students will be successful with that support; others may continue to struggle. At that point, diagnostic assessment — more thorough and specific than a screening — can help determine whether a struggling student has learning difficulties that require specialized instruction.

Ensuring that requirements are both effective and efficient can help states and districts spend funds wisely on screening tools and ensure that instructional time is not wasted on assessments that don’t help identify at-risk students.

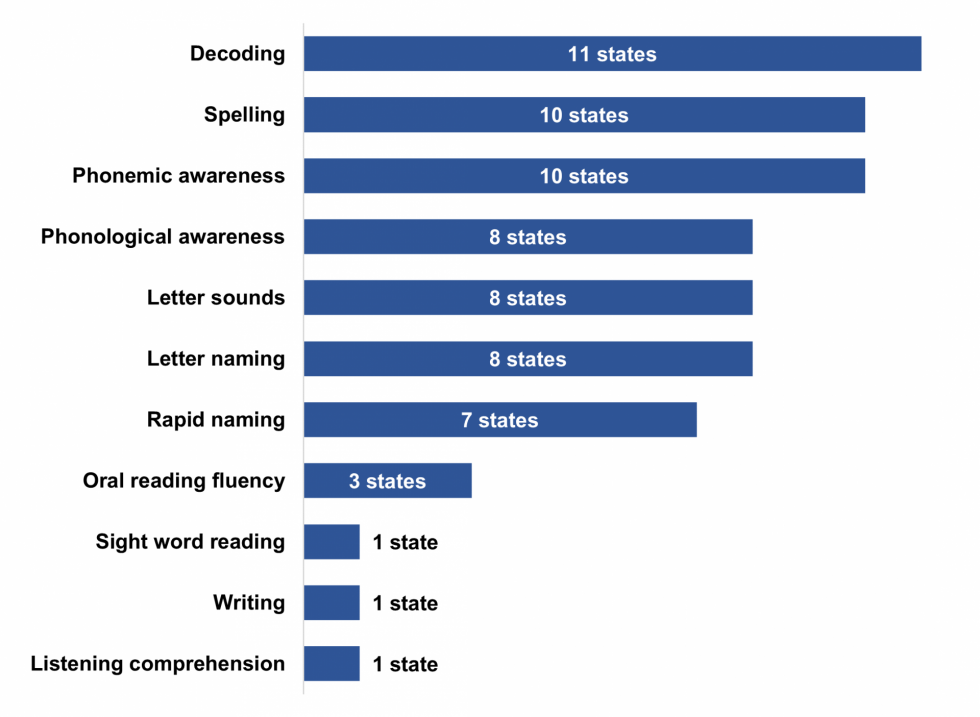

The idea of screening students in reading is not new, but state laws that require the screening to cover specific skills are. The required skills vary considerably between states, and most states require screening for the same skills for all students in grades K-3.

Skills That SREB States Require in Screening for Reading Difficulties/Dyslexia

Read the definitions and details about these skills and how states describe them below.

These requirements may not match the best practices identified by experts. Research continues to evolve, but the consensus right now is that the following skills are most predictive of reading achievement:

Kindergarten: phonological and phonemic awareness, rapid automatic naming (especially of letter names), letter-sound association and phonological memory

1st Grade: phonemic awareness (e.g., phoneme segmentation), letter manipulation, non-word repetition, oral vocabulary and word identification

2nd Grade: word identification (real and nonsense), oral reading fluency and reading comprehension

In later grades, oral reading fluency and reading comprehension tend to be the best indicators of risk for reading difficulties.

Some states may find that their requirements fall short of best practices. Other states may require screening for skills that don’t really help predict which students will struggle. Ensuring that requirements are both effective and efficient can help states and districts spend funds wisely on screening tools and ensure that instructional time is not wasted on assessments that don’t help identify at-risk students. States may want to examine their requirements and consult with experts to make sure their laws and guidance for schools meet their goals for improving reading achievement. And screening is just one element of a push to improve students’ reading proficiency. In a future post we’ll discuss one major consideration that can hamstring a state’s attempts to help students with dyslexia.

Reading skills definitions:

- Letter naming is also referred to as alphabet knowledge and assesses a person’s ability to recognize lowercase and uppercase letters of the alphabet.

- Letter sounds is also referred to as sound-symbol recognition and assesses a person’s ability to name the sound(s) each letter of the alphabet represents.

- Phonological awareness is the understanding that words are made up of sounds. It can be demonstrated through rhyming, discrimination between the starting or ending sounds of two similar words, and recognizing the number of syllables in a word.

- Phonemic awareness is the ability to hear and manipulate the individual sounds in words. This can be demonstrated through tasks like blending separate sounds together to make a word or adding or deleting sounds from one word to make another. Some states specify that screening must include specific phonemic awareness skills, such as phoneme segmentation.

- Decoding is the process of translating print into speech — using one’s knowledge of the sounds that letters and letter combinations represent to read words on a page. Some states specify that screening must assess phonics, nonsense word fluency or word reading accuracy. All of these are ways of assessing decoding skills.

- Sight word reading involves presenting a list of grade-appropriate words and assessing a person’s ability to quickly recognize them. This can also be called word identification.

- Spelling is also called encoding in some states’ screening laws.

- Rapid naming, also called rapid automatic naming or RAN, involves short, timed tasks that assess a person’s ability to quickly recognize and name shapes, letters, numbers, or other common symbols.

- Oral reading fluency measures how many words a person can accurately read from a text in one minute.

- The state that requires schools to screen for writing skills specifically requires that students be assessed for the ability to write using correct word sequences.

- Listening comprehension measures a person’s ability to understand what they hear.