Highlights From a Few of Our Featured Speakers

Promising Practices from the 2019 Making Schools Work Conference

The Opportunity Myth: How School Is Letting Students Down and How to Fix It

Classrooms are filled with

students whose big goals for their lives are slipping away each

day.

Classrooms are filled with

students whose big goals for their lives are slipping away each

day.

“That’s because we’ve been telling them that doing well in school creates opportunities — that showing up, doing the work and meeting teachers’ expectations will prepare them for their futures,” notes a report from TNTP (formerly The New Teacher Project). TNTP calls this gap between students’ goals and the messages we send them, “the opportunity myth.”

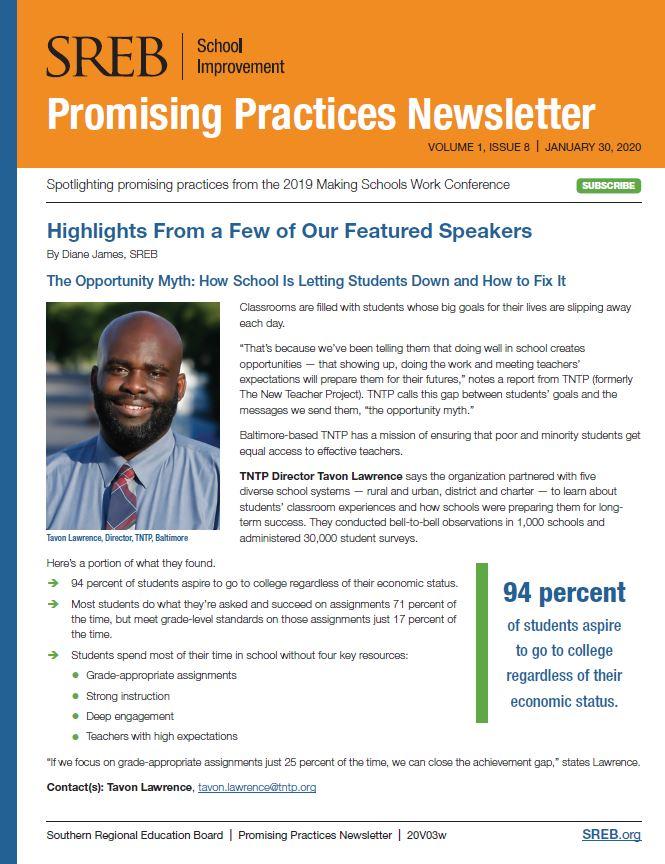

Baltimore-based TNTP has a mission of ensuring that poor and minority students get equal access to effective teachers.

Director Tavon Lawrence says the organization partnered with five diverse school systems — rural and urban, district and charter — to learn about students’ classroom experiences and how schools were preparing them for long-term success. They conducted bell-to-bell observations in 1,000 schools and administered 30,000 student surveys.

Here’s a portion of what they found.

• 94% of students aspire to go to college regardless of their economic status.

• Most students do what they’re asked and succeed on assignments 71% of the time, but meet grade-level standards on those assignments just 17% of the time.

Students spend most of their time in school without four key resources:

• Grade-appropriate assignments

• Strong Instruction

• Deep engagement

• Teachers with high expectations

“If we focus on grade-appropriate assignments just 25 percent of the time, we can close the achievement gap,” states Lawrence.

Contact(s): Tavon Lawrence, tavon.lawrence@tntp.org

Disrupting Poverty: Five Powerful Classroom Practices

The number of students living in poverty has been climbing over

the years and stands at an alarming rate. The U.S. Census Bureau

reports that as of 2016, nearly 60 percent of children age 5 to

18 received free- and reduced-price lunch — an indicator of

students’ socioeconomic status.

Poverty makes teachers’ jobs more challenging.

Kathleen Budge and William Parrett of Boise State University discussed their research and book, Disrupting Poverty: Five Powerful Classroom Practices, which examines classroom-tested strategies that make up the culture of successful high poverty schools:

1. Caring relationships and advocacy — “It’s critically important to get to know your kids,” says Parrett. Teachers may act as role models, mentors and intervenors.

2. High expectations and support — Parrett adds, “Teachers must have high expectations and believe kids can do the work.”

3. Commitment to equity — “Good teaching for all kids is good teaching for kids who live in poverty,” insists Budge.

4. Professional accountability for learning — Schools and teachers can’t cure or prevent poverty, but school can make a considerable difference in the lives of students who live in poverty, the authors maintain.

5. Courage and will to act — Educators who disrupt poverty have clarity about who they are as people and why they chose to become educators. They reject biases about people who live in poverty, set high expectations and provide supports for students to meet those expectations.

SREB’s Tokitha Ferguson contributed to this report.

Contact(s): Kathleen Budge, kathleenbudge@boisestate.edu; and William Parrett, wparrett@boisestate.edu

Poverty, Detached Parents and Apathetic Students

Too often, at-risk students, students from poverty and students who suffer from trauma are labeled as “slow,” as special education students or as students with learning disabilities. Such labels and qualifiers can prevent students from succeeding.

Craig Boykin, CEO, Craig

Boykin, LLC, isn’t shy about letting people know he was

one of those at-risk students who dropped out of school, endured

his mother’s drug abuse, had an absent father and was identified

as having a learning disability. But he’s inspiring educators and

students around the nation with his trademark slogan – “From GED

to PHD” – to send a message that educators should never give up

on any student.

Craig Boykin, CEO, Craig

Boykin, LLC, isn’t shy about letting people know he was

one of those at-risk students who dropped out of school, endured

his mother’s drug abuse, had an absent father and was identified

as having a learning disability. But he’s inspiring educators and

students around the nation with his trademark slogan – “From GED

to PHD” – to send a message that educators should never give up

on any student.

“Learning won’t take place until a relationship is formed,” notes Boykin. The first thing teachers should do to motivate apathetic students is form a relationship with them. “If you don’t like a student, you don’t have to let them know that,” he says. “If you make a mistake with a kid, apologize. You have to respect every kid or respect their situation,” Boykin adds.

He advocates what he calls “My Rs”: real, respect, relevance, resilience and relationship. Equity is also at the top of the list for getting students to achieve. He defines equity as giving every child what they need to be successful. Equality, he says, is treating every child the same. “Kids don’t need equality,” he insists.

Contact(s): Craig Boykin, craigboykin@gmail.com

Dealing With Bullies

About one in every four students in the United States has reported being bullied. What’s more, “no kid is exempt from being bullied or being a bully,” maintain Kari Hankins and Kristen Cassidy, designers of the Truth, Facts & Lies education programs known as B Curriculum, LLC.

The perception that only students

considered “different” or “weak” get bullied is a myth; popular

kids do, too, they say. By the same token, Hankins and Cassidy

warn against the assumption that a child cannot be a bully just

because he or she appears to be a “good” kid.

The perception that only students

considered “different” or “weak” get bullied is a myth; popular

kids do, too, they say. By the same token, Hankins and Cassidy

warn against the assumption that a child cannot be a bully just

because he or she appears to be a “good” kid.

The pair defines bullying as a pattern of behavior by a person or group of people who repeatedly and intentionally exert power over another person. It might involve making fun of someone, threatening or fighting someone, making a student do something they don’t want to do or posting something negative about a student on social media with the intention of hurting or embarrassing that student.

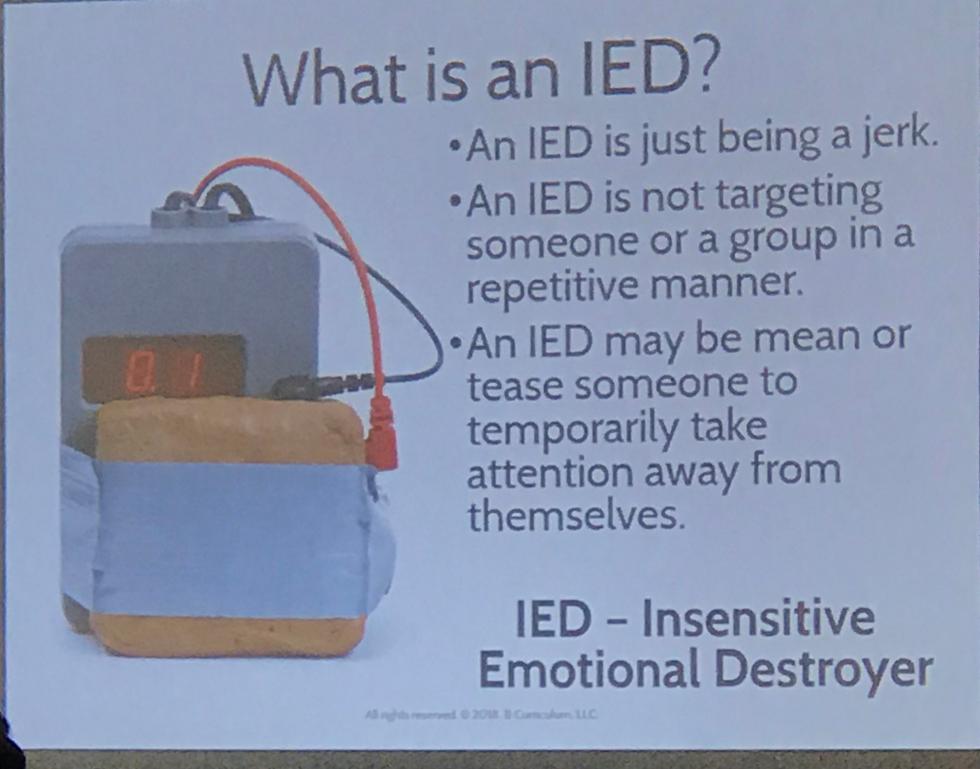

Some advice for adults who are trying to stop bullying: Hankins and Cassidy recommend not confusing a bully with a person classified as an Insensitive Emotional Destroyer (IED). IEDs are usually mean to others as a way of temporarily diverting attention away from themselves, they state. Hurting others is not their primary goal.

When an IED is confused as a

bully, a false sense of “a bullying epidemic” can surface in a

school, they report.

When an IED is confused as a

bully, a false sense of “a bullying epidemic” can surface in a

school, they report.

To stop bullying and negative behaviors, Hankins and Cassidy say it’s important for students to have support — a reliable person who they can turn to for help and can advocate for them.

SREB’s Quinton Granville contributed to this report.

Contact(s): Kari Hankins, kari@truthfactslies.org; Kristen Cassidy, kristen.couch24@gmail.com