Dyslexia Policy: The Changing Landscape

What does research say about how children should learn to read?

Research shows that beginning readers need to be taught how oral speech connects to written language. In order to understand that, young children must be able to perceive the individual sounds in spoken words — like the /c/ /a/ and /t/ sounds in “cat.” They must also be taught how those individual sounds correspond to written letters and combinations of letters, a skill called phonics. Some children learn these relationships quickly and easily, while others — approximately 40 percent of children — require explicit, systematic instruction.

Scientific studies have shown that skilled readers decode — or sound out — words accurately and automatically as they read. They may guess at the meaning of words they do not know, but they do not guess at the sounds that make up those words. For the 40 percent of children who require explicit instruction in reading, systematic phonics instruction is essential for accurate and automatic decoding. The National Reading Panel’s summary of findings reported in 2000 that “systematic phonics instruction produces significant benefits for students in kindergarten through 6th grade and for children having difficulty learning to read.”

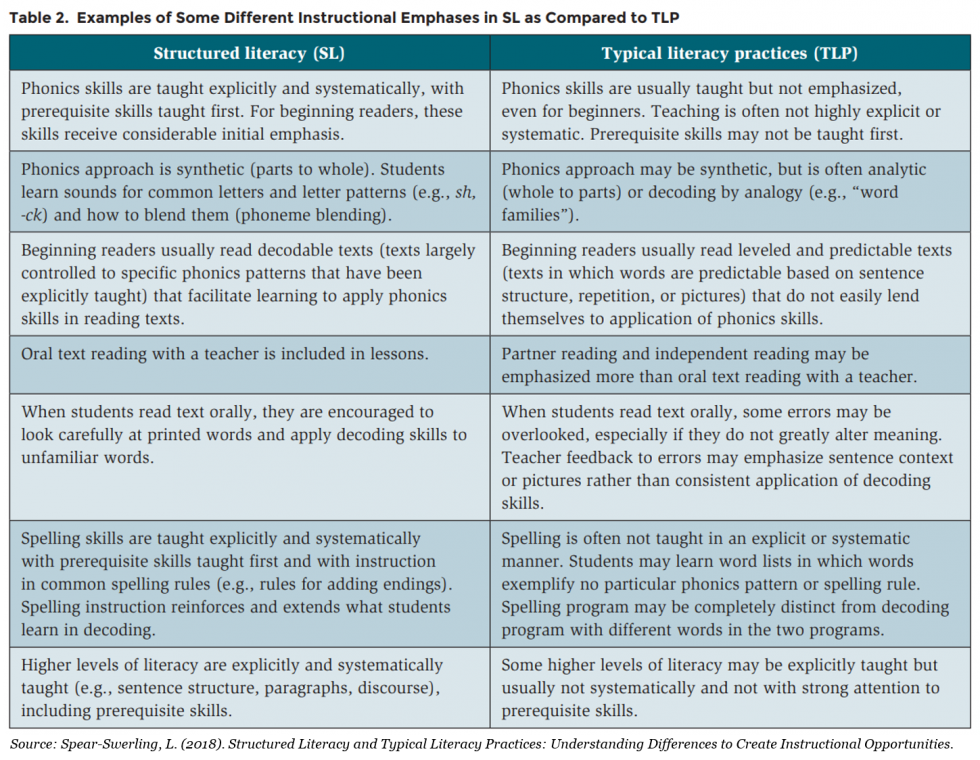

The International Dyslexia Association advocates for all students, but particularly students with dyslexia, to receive effective core reading instruction using a structured literacy approach. Structured literacy involves explicitly and systematically teaching elements of reading and English, including phonology, morphology and semantics.

Reading instruction in the early grades commonly uses methods that teach students to guess at words they do not recognize based primarily on context and sentence structure, rather than emphasizing the importance of fully sounding out an unknown word to see whether it is already in the their oral vocabulary. This form of instruction relies on a theory that children will discover naturally that they need to know about letter-sound relationships as they practice reading and writing and that teachers should provide incidental phonics instruction when they think students need it. This philosophy of reading instruction fails to provide some students with strong decoding skills and leaves them without reading strategies that work as they start to read more complicated texts with no pictures and little context.

For more information, see pages 2-101 to 2-107 in the National Reading Panel report.

What does research say about dyslexia screening?

Based on a number of different scientific studies, there are several grade-level skills that most accurately predict future reading performance:

- Kindergarten: phonological awareness (especially phoneme segmentation), letter sound knowledge, rapid automatic naming (of letters)

- First grade: phonological awareness (especially phoneme segmentation), rapid automatic naming (of letters)

- Second grade and up: oral reading fluency and reading comprehension

What should states know about dyslexia intervention?

Many types of dyslexia intervention programs are available. They tend to fall under the umbrella of multisensory structured language, which can also be called structured literacy. A multisensory approach to learning the structure of the English language, including reading, has been shown to rewire the brain of individuals with dyslexia to help bypass the areas responsible for reading difficulties. The most well-known approach to intervention, considered the “gold standard” for students with dyslexia, is the Orton-Gillingham Approach. Other major methods that are based on Orton-Gillingham principles include Wilson Reading, Barton, and Lindamood Bell programs. Various organizations and researchers have created other proprietary programs and curricula based on Orton-Gillingham. Commercial programs that incorporate multisensory teaching are also available.

The International Dyslexia Association’s Matrix of Multisensory Programs is a resource for identifying potential dyslexia intervention programs for schools. The National Center on Intensive Intervention’s Academic Interventions Tools Chart allows users to compare information on various reading intervention programs. EvidenceForESSA.org provides a summary of the scientific evidence backing some reading intervention programs.

What should states know about teacher training for addressing dyslexia?

Noteworthy, although not scientific, surveys and studies completed by entities such as Maryland’s Dyslexia Task Force find that misunderstandings about dyslexia are common among educators. These misconceptions include:

- Educators cannot/should not diagnose dyslexia;

- Dyslexia cannot be identified until a child is far behind in reading; and

- All students with dyslexia need special education.

Training for both preservice and current teachers should address these and other misconceptions and equip teachers to recognize possible signs of dyslexia in their students. Training should also ensure that teachers know the benefits of direct, explicit instruction in the five components of reading — phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency and comprehension — and are prepared to teach systematic phonics to students in kindergarten and first grade. Ideally, teachers will also know how to incorporate multisensory strategies into their classrooms, as these strategies benefit all students. The International Dyslexia Association’s Knowledge and Practice Standards for Teachers of Reading can serve as a basis for teacher preparation and teacher training.

SREB has compiled free online and state-by-state resources for teacher training on effective reading instruction and dyslexia intervention, available at www.sreb.org/dyslexia/training.

For more information, contact Samantha Durrance at 404-962-9639 or Samantha.Durrance@sreb.org.