Don’t Be Afraid to Say “Dyslexia”

Acknowledging and identifying dyslexia is step one in helping struggling readers

Researchers estimate that dyslexia affects at least one in 10 people. As defined by the International Dyslexia Association, dyslexia is a neurobiological learning disability, unrelated to intelligence, characterized by differences in the way the brain processes language. These differences result in difficulties developing skills that are important for reading and writing. While it cannot be outgrown, individuals with dyslexia can learn strategies to help them overcome the unique challenges it presents.

Dyslexia often reveals itself first in elementary school, when children experience persistent difficulty with specific literacy skills. These might include learning letter-sound relationships, sounding out unfamiliar words, spelling, or copying text. Young children with dyslexia may have delayed speech and struggle with language skills like rhyming before they even enter school. A number of websites, including that of the Dyslexia Resource Trust, provide more comprehensive lists of challenges common to individuals with dyslexia.

Despite its prevalence, the Dyslexia Research Institute estimates that only one of every 20 people with dyslexia is identified.

Despite its prevalence, the Dyslexia Research Institute estimates that only one of every 20 people with dyslexia is identified. The rest may have a hard time with reading, writing and spelling but never know why these subjects are so difficult for them. As a result they may never receive the specialized instruction that would help them become more successful readers and writers. Systematically identifying students with dyslexia and intervening early can make a difference for them and could raise the percentage of students who meet reading benchmarks. Researchers reported in 2008 that providing appropriate reading instruction and intervention for young children by second grade could reduce the percentage of students at risk for continuing reading difficulties to less than 5 percent.

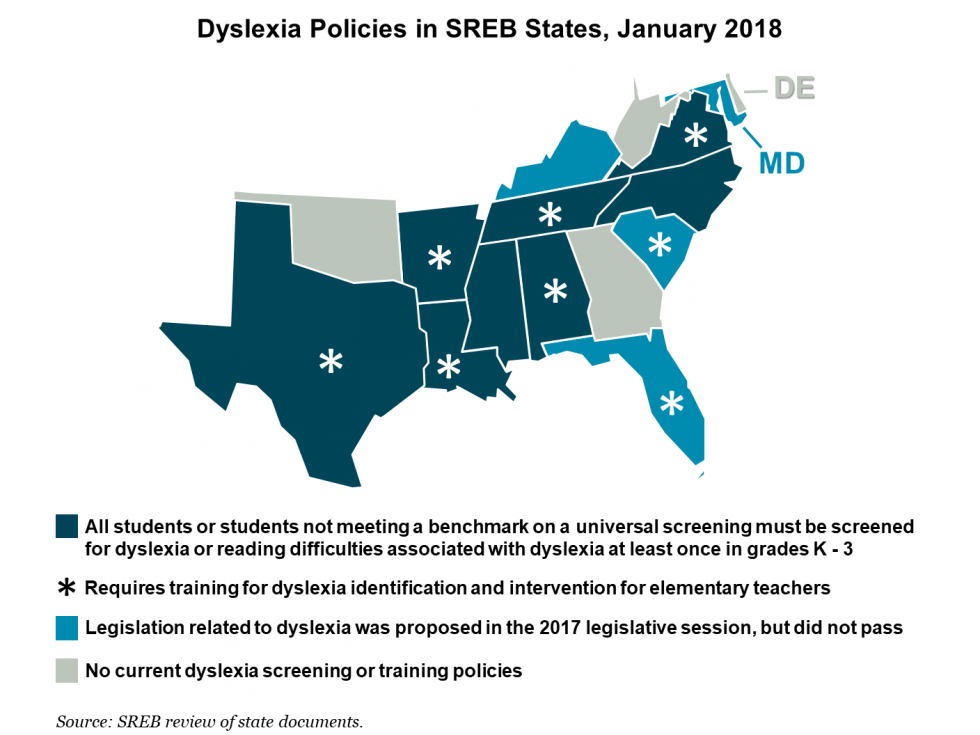

State policies related to dyslexia have advanced both nationwide and in the SREB region, especially during the past five years. (See map.) But despite this progress in state policy, misunderstandings about dyslexia are still common. In 2015, Maryland’s Dyslexia Task Force produced a report that examined current practices in the state and identified a number of common misconceptions among school personnel. Parents reported being told, for example, that educators were not allowed to use the term dyslexia because it is a medical diagnosis, that dyslexia cannot be detected until a child is in third grade and two years behind in reading, and that the identification of dyslexia is not required by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. The task force also reported that only 30 percent of teachers said they learned about dyslexia in their teacher preparation programs.

All students gain when educators know how to recognize dyslexia and use proven methods to teach students who struggle with reading. For more on what SREB states can do to ensure that children with dyslexia learn to read proficiently, read our new brief: Dyslexia Policies in SREB States.

Did you miss our November 2017 report on reading in the early grades? Ready to Read, Ready to Succeed explains what states can do to ensure that all students can read well by the time they enter fourth grade.