Are teachers prepared to teach reading?

Research shows a gap between what we know about reading and how teachers are prepared to teach it

Reading is the foundation for learning.

The research is clear: Students who are not reading proficiently by the end of third grade are much more likely to face poor academic outcomes. For this reason alone, we know it is incredibly important that children learn to read well early in elementary school and continue to build on those reading skills throughout the rest of school.

The task of teaching young children to read falls to elementary school teachers, especially teachers in kindergarten through third grade. But the methods used to teach reading vary, and so does the expertise of these teachers.

“Teaching children how to read is job one for elementary teachers because

reading proficiency underpins all later learning.”— National Council on Teacher Quality

Educators have argued for decades about which methods for teaching reading are the most effective. Some favor “whole-language” or “whole-word” programs that teach children to recognize and use words in context. Others assert that approaches based in phonics, which teach children to decode (sound out) words are better. There are many types of curricula and other resources available, all of which purport to be the best. School curricula have changed over the years as the pendulum swung back and forth.

Best practices, grounded in research

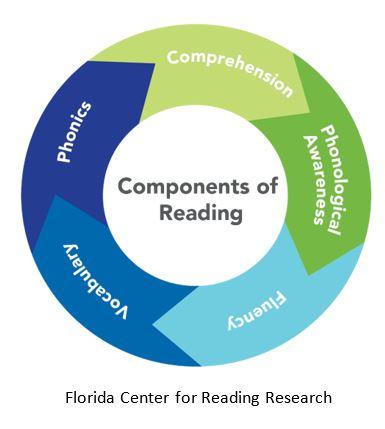

In 2000, the seminal National Reading Panel published important conclusions on best practices for teaching young children to read after examining a wide body of research on scientifically based teaching strategies and the effectiveness of different approaches to reading instruction. Researchers now know that all students need instruction in five major components of reading: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

The National Reading Panel found that younger students benefit most from instruction in sound identification, matching, and the segmentation and blending of phonemes. Networks of new vocabulary words need to be taught in context, not through memorization. And compared to other approaches to teaching early reading skills, systematic phonics instruction leads to greater gains for children in kindergarten through 6th grade, as well as for children who have difficulty with reading.

The National Reading Panel found that younger students benefit most from instruction in sound identification, matching, and the segmentation and blending of phonemes. Networks of new vocabulary words need to be taught in context, not through memorization. And compared to other approaches to teaching early reading skills, systematic phonics instruction leads to greater gains for children in kindergarten through 6th grade, as well as for children who have difficulty with reading.

Effective reading instruction, especially for struggling readers, must be explicit. Teachers need to clearly model strategies and specific skills and demonstrate processes, step-by-step. Effective instruction is also systematic: carefully sequenced by skill difficulty and paced in a way that provides students with sufficient time for mastery before moving on to a more challenging skill. Finally, good reading instruction provides many opportunities for guided practice and teacher feedback.

A recent report from the Institute of Medicine and National Research Council explains that in addition to the five essential components of reading instruction, educators must also have training that prepares them to teach more advanced literacy skills, including listening comprehension, reading comprehension, and learning content through reading. Skilled teachers can scaffold their students’ use of language by building from what they know and providing increasingly difficult prompts and questions that are appropriate for the word knowledge of each child. Doing all of this well requires practice and training.

Teachers can’t teach what they don’t know.

Teacher preparation programs need to make sure their elementary teacher candidates understand how children learn to read.

Teacher prep: more focus on reading instruction

Teacher preparation programs have been slow to close the gap between their preservice curricula and what research says about teaching reading. In 2010, researchers with the Institute of Educational Sciences surveyed more than 2,200 preservice teachers about how much their preparation programs focused on the essential components of reading instruction. Only 25 percent of the preservice teachers in the IES study reported that their preparation programs included a strong overall focus on reading instruction. Participants were twice as likely to report a strong focus on reading instruction in their preservice teaching experiences as in their preservice coursework.

The National Council on Teacher Quality finds additional evidence that preservice training for reading instruction is not adequate in many teacher preparation programs. The Council’s most recent evaluation of more than 800 undergraduate programs for elementary teacher education determined that only 39 percent of programs examined included instruction in all five essential components of reading. Nearly 1 in 5 programs examined addressed one or none of the components. However, this rate is on the rise nationwide and has increased by 10 percentage points since 2014. Some teacher education programs in SREB states are doing particularly well: six of the 13 programs recognized in the NCTQ report for their “A+” preparation for teaching early reading skills were in the SREB region.

Teachers can’t teach what they don’t know. Teacher preparation programs need to make sure their elementary teacher candidates understand how children learn to read, as well as how to help students who struggle with early literacy skills. States should ensure that elementary teachers are well-prepared to teach all aspects of reading and have access to high-quality curricula and resources that are evidence-based.

For more on how states can support student reading in the early grades, watch for our upcoming policy report: Ready to Read, Ready to Succeed.

_________________________________________________________________

The six teacher preparation programs that were recognized by NCTQ in 2016 for their “comprehensive and efficient instruction in the five essential components [of reading], with all required courses and textbooks supporting that effort”, are: Nicholls State University, Louisiana

University of North Carolina at Charlotte

Winthrop University, South Carolina

University of Texas at Arlington

Fairmont State University, West Virginia

West Liberty University, West Virginia